James Mangold’s A Complete Unknown follows the formative years of Bob Dylan from teen folk artist to rock star. The writer/director tells Screen about the film’s own five-year journey.

James Mangold recalls being “instantly and insatiably hooked by the possibilities” when he found the project that would eventually become A Complete Unknown.

It was autumn 2019, on a flight to Telluride Film Festival, that Searchlight Pictures executives showed Mangold a script they were acquiring that dramatised Bob Dylan’s arrival in New York as a 19-year-old folkie hopeful and emergence four years later, with his infamous electric set at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, as a full-on rock star.

“I didn’t even wait to ask whether I could have the movie,” says writer/director Mangold, who previously made Johnny Cash biopic Walk The Line. “I just started looking at the script, voraciously making notes.” A week later, “I had already started trying to write on it myself.”

Authored by Jay Cocks and based on Elijah Wald’s non-fiction book Dylan Goes Electric: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, And The Night That Split The Sixties, the script had been created for a planned HBO movie. Mangold found “wonderful scene work” in it, but he also wanted to dig deeper into certain aspects of the story.

Working at first with Cocks — who shares screenwriting credit with Mangold on the finished film — and then on his own, he began to remould the script to explore Dylan’s formative years in New York and his relationships with folk-scene father figure Pete Seeger (portrayed in the film by Edward Norton), scene queen Joan Baez (Monica Barbaro) and artist-activist Sylvie Russo (Elle Fanning, playing the film’s surrogate for Dylan’s real-life first love Suze Rotolo).

“I felt strongly that there was a kind of fable, a kind of fairy tale in the story of this young man arriving with a new name and stories about working at the carnival, a fable that it might be possible to articulate without falling into standard biopic tropes,” says Mangold.

Making sense of Dylan’s “acting out” as his fame exploded would only be possible, the filmmaker suggests, “if I fully understood what he was pushing against, or trying to escape. I thought there was a level of understanding Bob that could happen by watching him navigate those early years.”

While he was writing, Mangold also began what he describes as a protracted “dance” with lead Timothée Chalamet.

Hot off Call Me By Your Name and other buzzy features, Chalamet had been circling the Dylan project before Mangold’s involvement. When director and star had their initial meeting, the proposed casting “seemed brilliantly right to me”, says Mangold, although the actor would still need to show he could learn to play guitar and harmonica and sing as Dylan — which he does with impressive skill in the film, almost always live rather than on a pre-recorded playback.

Mangold acknowledges that Chalamet “did a huge amount of work, not just musically but also in watching the way Bob moved and walked and gestured and trying to integrate that into his own personality”.

Director and actor also worked together to shape the film’s portrayal of its famously elusive subject. “For five years we talked about this character, about how [Chalamet] would think about this character, how he would play this character,” explains Mangold. “I had a theory that I talked to Timmy about, that [the film’s Dylan] should always be writing, that there would be a part of him that is separating from the people around him and kind of voyaging in his mind.

“I wanted Timmy threading something from the very beginning, so when he finally gets to the point of intense stardom and this level of adulation or rejection is coming at him from the audience, he’s already put up a kind of barrier, almost out of an act of self-preservation. That was something we charted very carefully.”

Personal touch

Another important contributor to the film’s depiction turned out to be Bob Dylan himself. The project had secured the co-operation of Dylan and his manager Jeff Rosen — who serves as a producer of A Complete Unknown, along with Mangold, Chalamet and five others — when it was first set up at HBO, ensuring the film could include performances of any song Dylan had written between 1960-65.

But the Dylan camp still had to sign off on a script, and when Mangold was reworking Cocks’ screenplay he realised that “part of what Jay had been avoiding was probably out of their instruction not to get into [Dylan’s] early personal life in New York. I came in a little more like a ton of bricks and wrote the movie I thought should be done. And it did set off some alarms.”

When Dylan himself read the script, however, “he liked it”, says Mangold. “That immediately lifted the stress around what I’d done and where I had gone.”

During the Covid lockdowns, the filmmaker had a series of meetings with the intensely private singer/songwriter. “Just the two of us in a coffee shop in Santa Monica that had been closed due to the pandemic,” says Mangold. “He was really open with me, and we talked about everything from my other movies to novels and history and also his own feelings about this period. I felt like there were a lot of unique perspectives I got from him that might not have been integrated in any existing biographies.”

The only change Dylan requested, according to Mangold, was that the film not use Rotolo’s real name.

For Mangold, the conversations with Chalamet and Dylan were silver linings to a pandemic cloud that caused the first of several delays to shooting what was then referred to as Going Electric. After the lockdown, the in-demand Chalamet had to fulfil previous commitments to star in Bones And All, Wonka and Dune: Part Two. Mangold took the opportunity to go to the UK to direct Indiana Jones And The Dial Of Destiny.

After the shoot was pushed again in 2023 by the US actors strike, A Complete Unknown eventually began production in March 2024, with locations in New Jersey, just across the Hudson River from New York City, standing in for the story’s early-1960s Greenwich Village settings.

Faced with either finishing in time for a December release or waiting for a date during the 2025-26 awards season, Mangold opted for the former, “because films like this are fragile”, he says. “It’s hard to protect something sitting fallow for that long.”

His confidence was boosted by the cut he was able to show Searchlight just two-and-a-half weeks after filming wrapped. “You could see the performances and the world were working,” he says. “That tells you more than any calendar can tell you.”

Released by Searchlight Pictures in North America on Christmas Day, with an international rollout through Searchlight parent Disney beginning in January, A Complete Unknown has made a late entry to awards season, picking up three nominations apiece at the Critics Choice Awards and Golden Globes, including for Chalamet and Edward Norton at both awards.

In the pipeline

Mangold, meanwhile, insists that for the first time in six or seven years he currently has no idea what his next film will be, though he confirms he is still working on scripts for a number of projects, including a take on DC Comics character Swamp Thing and, with Beau Willimon, the Star Wars: Dawn Of The Jedi prequel.

With a writing and directing filmography that takes in mental-health drama Girl, Interrupted, western remake 3:10 To Yuma, superhero smash Logan, race-car outing Ford v Ferrari and biopic Walk The Line (whose subject Johnny Cash also shows up in A Complete Unknown), Mangold is hard to pigeonhole and not eager to help an interviewer making the attempt.

“It’s probably not healthy for me to try to articulate for a journalist what makes my movies mine,” says a filmmaker whose features have netted their actors Oscar nominations (Joaquin Phoenix in Walk The Line) or wins (Reese Witherspoon in Walk The Line, Angelina Jolie in Girl, Interrupted), but whose own two Oscar nods have come in creative disciplines other than directing: best picture in 2020 for producing Ford v Ferrari and best adapted screenplay in 2018 for Logan. He has yet to receive any personal recognition from Bafta.

“I don’t feel like I am a different director when I’m making Logan than I am when I’m making A Complete Unknown,” he adds. “And I look forward to making both kinds and scales of movies in the future.”

Whereas his filmmaking heroes — from Billy Wilder to Sydney Pollack — moved easily among genres, today “we grasp for such easy answers about what writers and directors are”, suggests Mangold. “Even as directors we sometimes feed the machine by fastidiously applying our ‘touches’ in ways that signify, ‘It’s me, I’m still here’.

“Maybe because I’m a writer, I feel like I’m speaking through the characters and the scenes and the way I move the actors. But I try not to make it so that you’re aware, thinking about the application of directorial style. That, I’m not interested in.”

Artistic statements: Bob Dylan on film

Scripted and unscripted, as both performer and subject, the musician has enjoyed a rich screen history

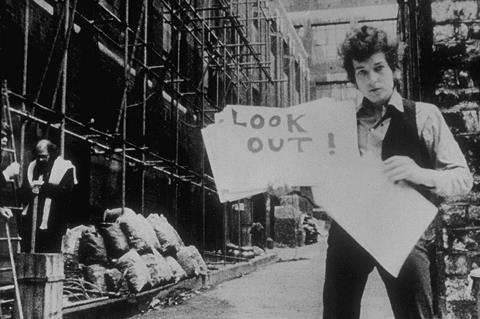

Dont Look Back (1967)

Direct-cinema pioneer DA Pennebaker followed Dylan on his pivotal 1965 solo tour of the UK to make this classic black-and-white documentary, using handheld cameras to capture on-stage performances as well as off-stage interactions with musicians, fans and journalists. Also appearing in the mispunctuated-title film are several of the real-life characters played by actors in A Complete Unknown, among them Joan Baez, Albert Grossman and Bob Neuwirth.

Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid (1973)

Dylan made his acting debut in Sam Peckinpah’s revisionist western for MGM, in the small role of an outlaw sidekick to James Coburn and Kris Kristofferson’s title characters. He also contributed music and songs — including hit ‘Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door’ — to the soundtrack, earning himself Bafta and Grammy nominations. Panned on its initial release, the film was reappraised in later decades, and a restored version screened at the Berlinale in 2006.

Masked And Anonymous (2002)

Using the pseudonym Sergei Petrov, Dylan co-wrote this BBC Film-backed comedy drama with director Larry Charles. The cast includes Jeff Bridges, Penelope Cruz, John Goodman and Jessica Lange, with Dylan playing the part of Jack Fate, a singer sprung from jail by shady promoters for a benefit show in a revolution-torn country. With a soundtrack of Dylan songs played by himself and others, the film premiered at Sundance Film Festival but drew mostly dismissive reviews and meagre box office.

I’m Not There (2007)

Writer/director Todd Haynes used six different actors — Christian Bale, Cate Blanchett (pictured), Marcus Carl Franklin, Richard Gere, Heath Ledger and Ben Whishaw — to play different aspects of an elusive central character in his fictionalised bio-drama inspired, according to the credits, by Dylan’s “many lives”. Dylan approved the approach and allowed the use of his songs, which are mostly performed by other artists. An official premiere at Venice Film Festival, where Blanchett won the best actress prize, was followed by a $12m worldwide box-office run.

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story By Martin Scorsese (2019)

Scorsese, who previously covered Dylan in TV documentary No Direction Home, assembled this playful mix of fact and fantasy using restored footage from Dylan’s 1975 Rolling Thunder tour and contemporary interviews with Dylan and other tour participants, some real, some fictional. Providing an alternative to the little-seen Renaldo And Clara, the rambling Dylan-directed drama also shot on the tour, the Netflix film picked up three nominations at the 2019 Critics’ Choice Documentary Awards.

No comments yet